What began as a modest chess programme in a Chicago jail has grown into a worldwide movement. The fifth edition of the FIDE Intercontinental Online Chess Championship for Prisoners has set a new participation record, with 135 teams from 57 countries competing between 14th and 16th October.

The first chess programme for inmates and detainees was launched by the Cook County Sheriff’s Office in Chicago in 2012. In 2019 they organised their first international tournament. Two years later, they partnered with FIDE. Since 2021, the International Chess Federation and Cook County Sheriff’s Office have been working together on the “Chess for Freedom” programme, aimed at inmates across the world, helping them learn essential life skills through chess.

The central event of the programme is the FIDE International Online Chess Championship, which has over the years attracted teams from nearly 60 countries worldwide. The event is held around the mid-October to coincide with the celebration of the International Day of Education in Prison. Observed on 13th October, it highlights the importance of education in correctional facilities as a fundamental human right and a pillar for rehabilitation and improvement.

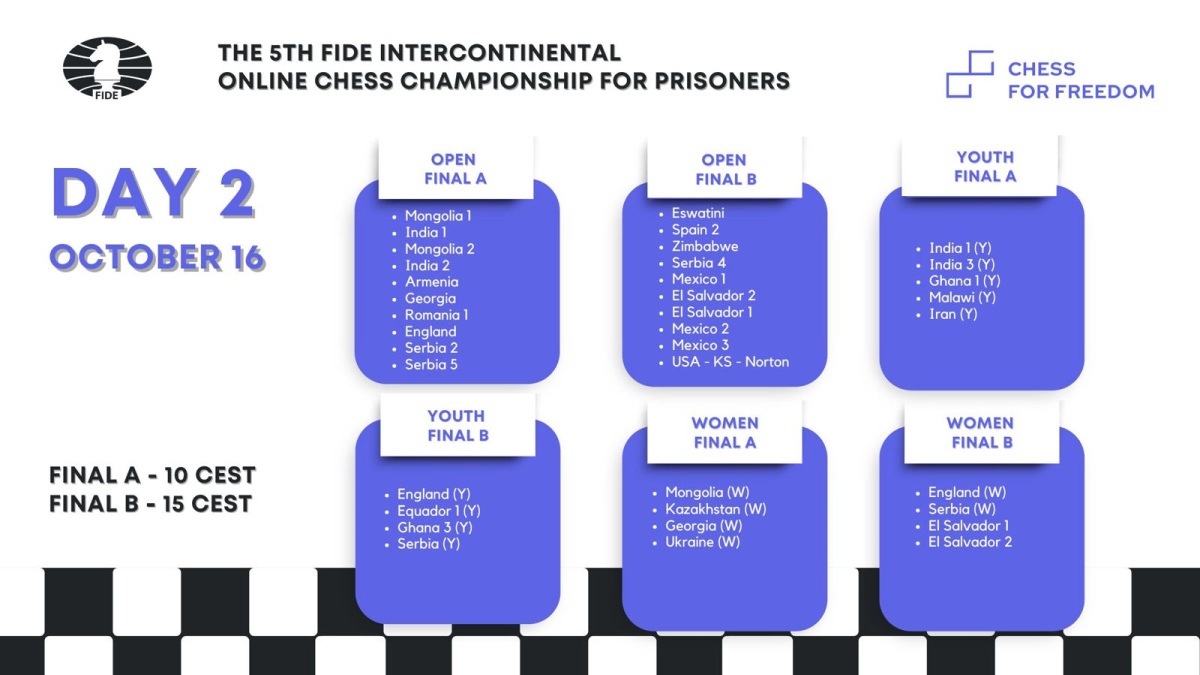

The fifth edition of the Championship for Prisoners takes place between 14th and 16th October and is one of the final events in the Year of Social Chess, which highlighted the role of chess as a tool for inclusion and empowerment. The competition is split into three stages – the group stage (14th), the championship stage (15th) and the finals (16th).

This year set a new record, with 135 teams from 57 countries taking part. The lineup includes 89 teams in the Open section, 26 in the Women’s, and 20 in the Youth. Several countries are making their debut, among them Eswatini, Guyana, Lesotho, Poland, Aruba, and St. Kitts and Nevis. Each team has four players, and the games are played entirely online with 10 minutes for each player plus a five-second increment from move one.

“We all make mistakes in life. But as long as we are alive, we can learn”

The event was opened by FIDE President Arkady Dvorkovich, who said that playing chess offers a direct path to self-motivation, logical thinking, stress reduction, and foresight of consequences, all “important pillars for a good life”.

“We are all human. We all make mistakes in life. But as long as we are alive, we have a chance to learn from them and correct them. It takes a lot of courage to change, and that is why I want to warmly welcome you all on behalf of the entire chess community and thank you for taking part in this event”, said Dvorkovich in his message to the players.

Dana Reizniece, the Managing Director and Deputy Chair of the Management Board of FIDE, who has been deeply involved in social chess programmes around the world, explained why the governing body of chess decided to engage in this project.

“Chess teaches us focus, resilience and consistency. It sharpens the mind and allows us to channel the energy in a constructive way. Chess also gives hope. Hope that growth is possible, hope that change is possible.”

Global coverage

This year’s event is accompanied by a live broadcast which started at 6 AM CET and finished around 8 PM CET – nearly 13 hours in total. Apart from live commentary of the games, the broadcast featured special reports, presentations, and live conversations with guests from Australia to America who spoke about their experiences with the Chess for Freedom project.

The life of a chess player in prison: Experiences from Australia to U.S.

Tom Noiprasit works as an Education Services Coordinator at the Macquarie Correctional Centre, a maximum-security prison for male offenders located in Wellington, in the Orana region of western New South Wales, Australia. The facility has had a chess team for the past five years.

A software engineer and former consultant, Noiprasit moved to teaching before taking a position at the Macquarie Correctional Centre. He noted that a common misconception people have is that education in prison is about “fixing people,” when it is more about helping them develop skills.

As Noiprasit explains, the ambitions of people in prison are not much different from those on the outside – they want a job, a career, and they want to have a house to build their own life around.

“Our job is not to judge people in prison but to make sure when they come out, they can choose to be what they want to be.”

Different prisons have different rules when it comes to using computers for chess or anything else. In most cases, prisons do not allow inmates to use computers. Instead, they are given books and magazines where they can read about chess games and analyse. “It helps them talk to one another and practice social skills as well,” Noiprasit noted.

While access to the internet seems like an everyday thing for most people, it’s not the case for those behind bars. “Access to the internet is a big thing and you need to be fully supervising this,” says Noiprasit.

Prison officials also have to check very carefully who should be permitted to access the internet. “It could be anything – using the internet could bring up trauma, or an inmate who usually might not do a wrong thing might be tempted to do it.”

“Emotional self-regulation and, in particular, the ability to let go are the main skills relevant for inmates when it comes to chess,” Noiprasit concluded.

In Singapore, Grandmaster Goh Wei Ming – who visits prisons once a week to play chess – pointed out that “all inmates who participated in the Chess for Freedom programme exhibited much better behaviour, according to prison officers.”

“We had a case of a player who had very high blood pressure. When he was playing for the first time, he had a counsellor with him, reminding him to look after his blood pressure. Two years into the programme, he is now much calmer and off medication. It’s nice to know that chess can be therapeutic in that sense,” Ming said.

In the UAE – which is also participating in the Chess for Freedom project – inmates also get to enjoy chess classes and work with coaches. As the Secretary General of the Dubai Chess & Culture Club, Saeed Shakari explained, players have access to chess sets and online chess platforms where they can play and practice, thanks to strong support by the Dubai Police and their commander. This investment paid off, as in 2024 the UAE inmates won the open section of the Intercontinental Online Chess Championship for Prisoners.

“The inmates have improved over time. Some have left prison and have improved not just in chess but also in their everyday lives. Chess taught them how to act in life and to be responsible for their own decisions,” Shakari said.

In the Americas, the Chess for Freedom project has been a catalyst for opening broader educational opportunities for inmates. With Aruba and St. Kitts and Nevis joining the competition for the first time this year, the project has received wide backing from state stakeholders across the board. Jose Carrillo, FIDE Continental President for America, spoke to the broadcast and said that many of the inmates are provided with internet access and training to improve their chess skills.

“It’s a step-by-step process, and a growing number of local governments and organisations are getting involved. We love this project and see it growing. In El Salvador or Jamaica, for example, thanks to this programme we found very strong players among the inmates.”

Carrillo hopes that this initiative will help encourage other countries to get involved and, by extension, spread chess to more people.

Mikhail Korenman is a Project Manager and Social Commission Councillor at the Cook County Sheriff’s Department in the U.S. He has been a key instigator of the Chess for Freedom project since 2021.

“I was positively surprised by the first event in 2021, but I never expected it to grow to what it is today. Every year we get more new countries, and very few have dropped out, which is a good sign,” Korenman said.

In 2019, Cook County organised the first international chess tournament for prisoners with seven countries participating, “but for growth, we joined forces with FIDE, which has the system and the energy,” he explained.

Former inmate, Elifas Nyame: “Chess is life on board”

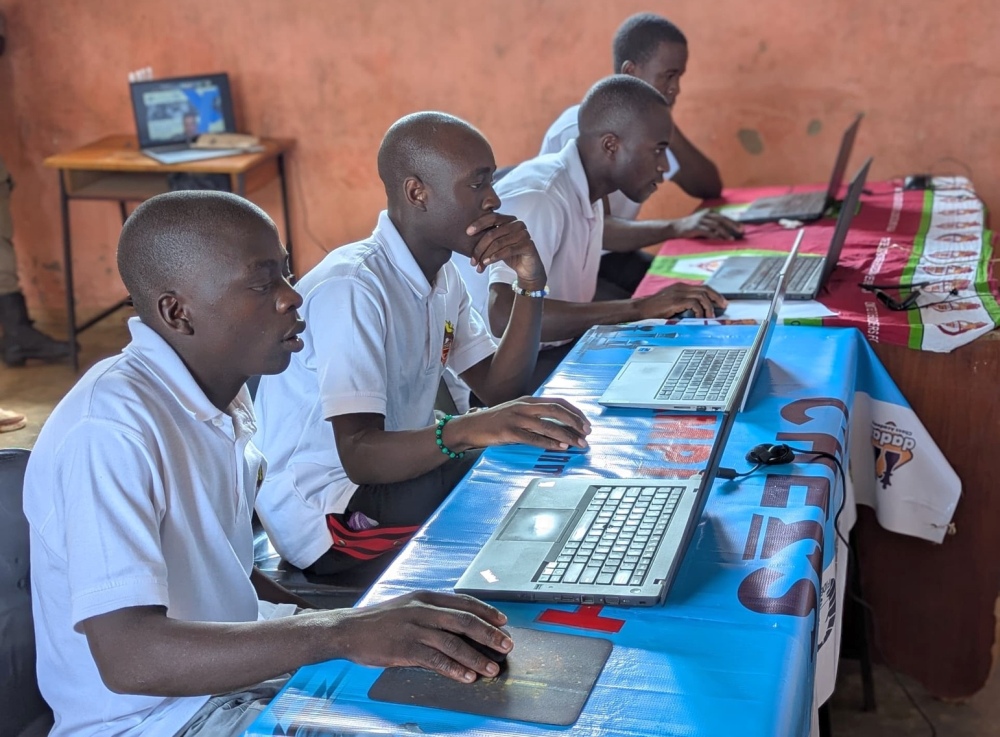

Internet access in Ghana is tied to urban areas, with about a third of the country still not having any connection. Elifas Nyame travelled more than five hours so he could take part in the live FIDE broadcast.

A former beneficiary from the Senior Correctional Centre and one of the students of the Chess for Freedom programme by run by the Mentors Chess Academy in Ghana, he shared what chess meant for him and his life.

“I learnt that life is not always about you, but also about others. Like in chess – you have to adapt to your opponents who are trying to do the same thing as you. It could be other people, it could be financial constraints, but there’s always something fighting against you. With patience and adapting, you can do it”.

Advice to anyone in similar circumstances who might take up chess? “Relax, have patience, think and play,” said Nyame who is now trying to get others to pick up the sport.

You can watch the full broadcast of the first day of the event on FIDE’s YouTube channel:

Results from the group stage

The first day of the tournament saw the group competition unfold with top two teams in each group qualifying for the second stage, which is held on Wednesday, 15th October.

The results of the group stage, across the Open, Women’s and Youth competition are as follows:

Open

Group 1 (Mongolia 1 and India 1 qualified)

Group 2 (Mongolia 2 and India 2 qualified)

Group 3 (Zimbabwe and Spain 2 qualified)

Group 4 (Serbia 2 and England qualified)

Group 5 (Armenia and Eswatini qualified)

Group 6 (Serbia 4 and Georgia qualified)

Group 7 (Serbia 5 and Romania 1 qualified)

Group 8 (Mexico 1 and El Salvador 2 qualified)

Group 9 (El Salvador 1 and Mexico 2 qualified)

Group 10 (Mexico 3 and USA – KS – Norton qualified)

Women

Group 1 (Mongolia and Kazakhstan qualified)

Group 2 (England and Serbia qualified)

Group 3 (Georgia and Ukraine qualified)

Group 4 (El Salvador 1 and El Salvador 2 qualified)

Youth

Group 1 (India 1 and India 3 qualified)

Group 2 (England and Ghana 3 qualified)

Group 3 (Ghana 1 and Malawi qualified)

Group 4 (Serbia and Ecuador 1 qualified)

Written by Milan Dinic